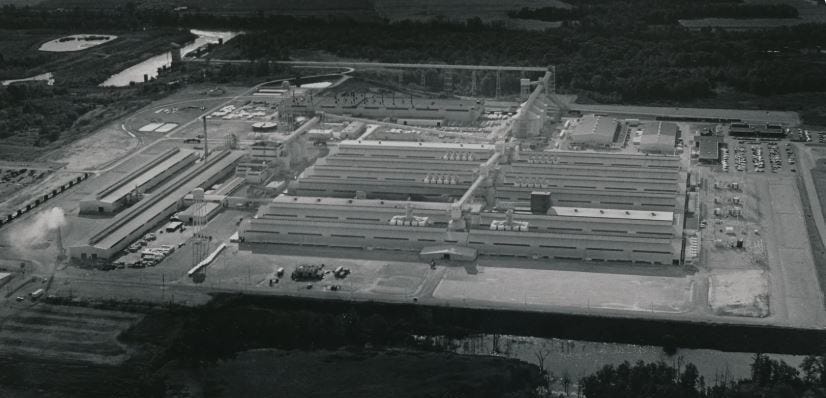

Anaconda Aluminum 1973 - Henderson County Library

By Ron Dodson | Conservation Chronicles

In the summer of 1973, I stood at a crossroads. My one-year teaching assignment at Henderson City High School had come to an unexpected end—not because I failed, but because the position had always been temporary. A detail that Bill Womack, the principal who hired me, conveniently left out. The teacher I’d replaced was returning from maternity leave, and just like that, I was out of the classroom.

With bills to pay and few teaching jobs on the horizon, I did what many of us do when life hands us a curveball—I adapted. A help-wanted ad in the Gleaner caught my eye. Anaconda Aluminum, a massive new plant under construction just down the road in Sebree, Kentucky, was hiring summer workers. It was supposed to be temporary. Just a few months, I told myself. A way to buy some time until a new teaching gig came along.

However, that temporary job evolved into a three-year experience that reshaped my perspective on work, people, and the complex incentives that influence our use—and misuse—of energy and resources.

From Chalkboard to Bag Houses

Anaconda hired me into their Environmental Department, where I helped install “bag houses”—massive filtration systems that captured air pollutants before they could escape into the sky. The company was aiming to be a model for air quality management in the aluminum industry. It was hot, dirty work, and I was green as could be. However, I learned a great deal—not just about aluminum smelting, but also about industrial systems, hierarchy, and how little of my formal education was applicable in this new environment.

By summer’s end, I was offered a full-time position, and without another teaching opportunity lined up—and with Theresa and me hoping to avoid yet another move—I said yes. Just like that, I was no longer a teacher. I was a factory man.

A Supervisor Who Couldn’t Weld

My role evolved quickly. Within a month, I became the supervisor of the Services Department. That meant overseeing a crew of electricians, welders, mechanics, and heavy equipment operators. There was just one catch: I couldn’t weld, didn’t know much about electricity, and had never operated a bulldozer. But I didn’t need to—I had people who did.

My job was to listen, assess, and send the right people to the right problems. When the plant ran into a snag—and it often did—I got the call on my walkie-talkie, day or night. We worked a rotating shift schedule that flipped my internal clock upside down. I hated that part. But I loved working with the crew—ordinary folks who came in every day to keep the place running.

Some were brilliant. Some were expert avoiders of anything that looked like work. Most fell somewhere in between. And in that mix of personalities, I got my first real education in managing people—a skill that would become essential later in my conservation career.

Turning Off the Lights—Then Turning Them Back On

One of the strangest lessons I learned at Anaconda came from an energy efficiency initiative I launched. Working the night shift gave me a unique view of the plant—and I noticed something odd. The entire place was lit up like a Christmas tree. Massive lights blazed across areas that rarely saw a soul. One especially glaring example was the conveyor belt that carried raw alumina from our port to a storage silo. It looked like a runway at O’Hare, and no one was ever up there.

I asked my supervisors if I could lead a lighting audit. With their blessing, we spent weeks identifying lights we could remove or replace with motion sensors. It worked—we dramatically reduced our energy use. Then came the punchline: our electric bill increased.

Why? Because of a utility rate structure that rewarded bulk use. The more kilowatts we burned, the cheaper each one became. So when we used less electricity, our cost per unit went up. The bean counters didn’t like that, and soon we were back out there—turning lights back on.

It was my first real lesson in the backwards incentives that can undermine environmental progress. It wouldn’t be the last.

An Industrial Microcosm of America

After three years, I knew industrial life wasn’t for me. The inefficiencies drove me crazy. The bureaucracy chafed. The rotating shifts were brutal. But I wouldn’t trade the experience.

Anaconda was a slice of America—diverse, imperfect, and full of stories. I supervised people of all races, backgrounds, skill levels, and motivations. I saw how hard people worked—and how hard some worked to avoid it. I learned how systems fail not just because of poor design, but because the rules reward the wrong outcomes.

Most importantly, I learned that I was meant to help build a different kind of system. One rooted in stewardship, not extraction. In clarity, not confusion. In incentives that actually make sense.

Anaconda wasn’t the end of something for me. It was the beginning.

Postscript

Today, when I talk to people about conservation and sustainability, I always try to remember that not everyone comes to these ideas from a classroom, a research lab, or a nonprofit. Some come from the floor of a factory, a rotating night shift, or a walkie-talkie crackling with bad news. My job—as it was then—is to listen, assess, and find the right tools for the job.

And sometimes, that means turning off a few lights—even if the bill goes up.